Spark, March 2012

| SPARK 15 Rutherford Place New York, NY 10003 |

||

| New York Yearly Meeting News | ||

| Volume 43 Number 2 |

The Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) |

March 2012 |

| Editor, Paul Busby | ||

Contents

- Activism and Spirit

- Seeking to Live Peaceably in This Moment …

- A Quaker Evangelist at Occupy Wall Street

- Occupy Buffalo and Buffalo Quakers

- Occupy Wall Street and Buffalo Quakers

- Participating as a Quaker in Occupy Faith NYC

- Let Your Life Speak All Day All Week

- Ministering to the Military

- Out of My Comfort Zone: VA Medical Center

- How Michele Bachmann Taught Me to Pray

- The Place in Between

- Why I Am a Fracking Abolitionist

- From Despair to Empowerment

- Opening Dialogue

- Quaker Activism Continues in May Spark!

- Around Our Yearly Meeting

- Join the Nightingales Again

- Work Hard, Play Fair

- Notices

- Spring Sessions

(opens in new window)

Activism and Spirit

Christopher Sammond, Poplar Ridge Meeting

Isaac Hopper, an ardent abolitionist whom we now admire for his passionate, uncompromising fight against slavery, was read out of (ejected from membership in) what is now 15th Street Monthly Meeting. John Woolman, whom many now describe as a “Quaker saint,” was anything but enthusiastically welcomed when he visited monthly and yearly meetings with his message challenging the practice of Friends holding people in slavery. Friends have had a very checkered history in recognizing and supporting Friends who have felt led to be engaged in movements that challenged the social norms. It has been hard for us to distinguish when someone was a prophet, when someone was “walking disorderly” (working in a way that is outside our accepted practices and norms as Friends), and when they were both. How do we integrate our practice as Friends with current movements that challenge the status quo as wrong and not of God?

The Communications Committee, aware of the substantial commitment of many Friends in both the antifracking and Occupy movements, invited articles about this work, especially focusing on one of the major spiritual pitfalls in working against injustice, that of demonizing one’s opponent. We received a wealth of submissions, many focusing on those two movements and some engaging the spiritual truth that “there is no ‘other.’” As we as a Society continue to engage in these two movements, and a wealth of other efforts addressing injustice, we will have many opportunities to integrate who we are as Friends with the wider social movements of our day. Perhaps these articles will help us do just a little better job of that than some of our forebears.

We received so many responses to this theme that we will be continue with more articles in May Spark.

Seeking to Live Peaceably in This Moment …

Shirley Way, Central Finger Lakes Meeting

…we hear God calling us to live peaceably, ourselves, in all our relationships.

—NYYM’s Worship and Action Group, July 2004

One wise Friend added, “We don’t get to choose which ones.” Yes. Of course. So simple and so difficult.

In seeking to live peaceably in all our relationships, our words and our actions matter. Our thoughts matter too. What we carry in our hearts gets put out into the universe. To hold hurtful, vengeful intention toward anyone is to send out negativity that affects all of us. Means never justify the ends. The means are the ends. We only have this moment. We are called to live peaceably in every moment. This is why worship is so important.

Worship brings us back to the divine center and there, in communion with God, with Spirit, we are healed. There, God teaches us that in letting go of the pain, we are freed. Freed and energized to move forward in joy, seeking to step more into the Light that feeds and nourishes.

The more we are able to live into the Light, the greater the challenges we face and the more we are grounded in Love (God, Spirit) to face those challenges. To listen deeply and to follow brings change, which is always scary but it also brings, in my experience, deeper relationship with Spirit, with God, and with my faith community that walks with me. We cannot do this alone. We cannot listen well alone. We need a faith community to walk with us, to listen with us, and to hold us accountable.

|

If the “calling” comes from a need to feed ego rather than from Spirit, we will get drawn into the fight, seeking to “win,” praying our “opponent” loses. We will do more harm than good. If, instead, it comes from God, we understand we are not in charge of the outcome. Our job is simply to live up to and into what work is clearly ours—no more, no less. The work of peace, social justice, stewardship of the planet in these times is overwhelming, and if we attempt to take it all on, we can only harm ourselves and others. Is it not arrogant to believe that our work is to “fix” everything? Our work is to listen—to continually listen and to follow when we are clear.

One of the first demonstrations I attended was a large pro-choice rally in Philadelphia. A small pro-life group had gathered at the periphery. Abrasive exchanges flew between the two groups, and I felt a hardening of my own heart toward the “other.” Lines were drawn inside me. I was right, they were wrong. I knew I needed to not be a part of this.

During the height of the war on Iraq, I sometimes attended a vigil at the Pentagon. We were a small group, silently holding signs, some praying, as thousands poured past us, arriving to work for another day. Most ignored us of course, at least outwardly. Some wondered aloud at our seeming lack of employment. Sometimes family members who had lost loved ones stopped to watch, sometimes to approach, sometimes with aggression. On each occasion, one from the vigil stepped forward, seeking to engage, to listen, to understand. To be prepared for such moments, we must be grounded in God, in Spirit, so that the words are not our words but instead come from Spirit.

I have been arrested a few times and held in a few jails and in one federal prison camp for three months. Following the call to civil resistance has been an important step for me. It immediately releases angst as I feel as though I am taking a real step, it has given me a public voice for a time and it put me in community with deeply spiritual activists. A test to help me determine my readiness for direct action is whether I am able to envision the entire process—from action, to arrest, to processing at the jail, to eventual release—and at the same time, hold each of the people I will encounter in that process in love. Can I hold them with a spirit of love, praying that they find peace and joy in their lives? If I am not in a place where I am able to do that, I am not ready for the action. I am not called.

Most people in prison carry unimaginable pain. To live there is to expose oneself to and to begin to take on that pain through secondary trauma. When I was incarcerated, daily worship with a Bible study group and the bond of friendship with other prisoners of conscience incarcerated with me helped me to be grounded much of the time and to thereby greet the inevitable conflicts with love.

For me, seeking to live as nonviolently as I am able in any given moment is a selfish act. I believe that we humans are all connected in the spiritual realm. So when I carry an intention to hurt another, I am hurting myself. I know this experimentally. When I seek to hurt another, I feel awful—whether I have committed any act or not. Carrying the intention is painful. It takes me out of the Light, away from God, and that is painful.

These days, my need to be right is where the edge lies for me most of the time. I see this edge in me defined with greatest clarity in interactions with people who are similar to me—engaged in similar work. Ego gets in the way. Perhaps I see myself in them. And so there’s always more work to do.…

I am so grateful for the Alternatives to Violence Project, where I practice what it means to live as nonviolent a life as I am capable at the moment. And I am grateful for my cofacilitators at Cayuga Prison. On-team, I receive so many learnings—mostly about how to let go and create space for others to shine and grow.

For me, forgiveness and compassion are always linked: how do we hold people accountable for wrongdoing and yet at the same time remain in touch with their humanity enough to believe in their capacity to be transformed?

—Bell Hooks

A Quaker Evangelist at Occupy Wall Street

by John Edminster, Fifteenth Street Meeting

A Holocaust survivor in my meeting used to say, “Hitler made me a Quaker,” and the memory of her tempts me to quip, “George W. Bush made me a street evangelist,” but I think the truth is that the Holy Spirit did. But it was my sense of powerlessness to affect my country’s mad plunge into war that led me to pray for something meaningful to do about it, and it was in prayer that I received my call to write the tract “Jesus Christ Forbids War” and distribute it in street demonstrations and later in other public places. That’s where my ministry of tracts started. When Islamophobia raised its grim head in Congress, I was led to write “Christians and Jews, Bless Your Muslim Brothers and Sisters” to pass out at a street rally to defend the Muslim community. On October 14, 2011, when New York’s mayor first threatened to evict the Occupiers from Zuccotti Park, I rushed down to the site before dawn to serve as a prayerful presence—first staying up late to compose and print out 60 copies of “Jesus Christ Offers an Alternative to Corporate Greed and Rage against It,” later revised as “A Lie Cannot Stand Forever.” The lie? The lie that selfish behavior in the marketplace can be trusted to promote the common good. The Occupy movement is sick of lies and wants truth. The Holy Spirit has truth to offer, the Truth that sets free, and all the Occupy encampments should be welcoming places for Truth’s ambassadors. My sense is that they are, except where anger deafens people to “love your enemy.”

|

| John Edminster, seated with beard, at Occupy Wall Street |

| photo by Linda Hill Brainard |

Though my tracts are generally provoked by current evils in society, they’re not protests against evil so much as advertisements for the good, which is why I’ve begun to call myself an evangelist—a herald of God’s Good News for the suffering. I do it mostly with the written word, though I try to “be ready always to give an answer” (1 Peter 3:15) or, as we say today, to deliver an elevator speech. Whether my speech mentions Jesus, or Friends, depends on the words the Spirit gives me.

“Jesus Christ Forbids War,” labored over with a committee’s help, was adopted by NYYM in 2006; but other tracts, generally conceived the night before they appear on the street, go into print before a committee can gather. Within the past year, a helpful Quaker attorney advised me how to identify myself as a Friend, in a short disclaimer footnote, without implying that I speak for any Quaker body. Yet I’d always want a prayerful peer review to screen for errors, a function once served by the meeting elders. To provide for a speedy review process, four of us recently constituted a mutual oversight committee, theologically diverse and spanning two meetings, for tracts and other acts of public witness.

Paul, under house arrest in Rome, asked faraway friends to pray that he speak boldly, “as I ought to speak.” (Ephesians 6:19–20) Today is another day to speak boldly to the world, and those called to it need the prayer support of all Friends who’ll offer it.

If we divide into two camps—even into violent and the nonviolent—and stand in one camp while attacking the other, the world will never have peace. We will always blame and condemn those we feel are responsible for wars and social injustice, without recognizing the degree of violence within ourselves. We must work on ourselves and also with those we condemn if we want to have a real impact. –Ayya Khema

Occupy Buffalo and Buffalo Quakers

Chris Barbera, Buffalo Meeting

The Occupy Wall Street movement has captured the imagination of the world with a prophetic call for equality and justice. 99% of the populace is being called to awaken from their captivity to the 1%. Jesus overturned the moneychangers in the temple just as Moses confronted the 1% of Egypt’s pharaohs. The “Arab Spring” was a catalyst for the “American Autumn.”

Occupy Buffalo was born on Yom Kippur, October 8, 2011, at Niagara Square. This was the day of the first “general assembly.” That night, several people slept there; that is, the occupation began.

The occupation of public space, the right to peacefully assemble, is our constitutional right. But this movement is deeper than that. It is the beginning of a worldwide paradigm shift and a profound critique of the American, and all, empires. It is the beginning of a social reorganization and integration of new visions and worldviews of cooperation, harmony, and peace. It is the eschatological moment in Christian consciousness, the beginning of a new Mayan calendar cycle, and the birth pangs articulated by the prophet Isaiah. It is all of this and more. And practical actions are being taken every day to incarnate these ideals.

Buffalo Quakers have overwhelmingly supported the Occupy movement, and their quiet participation remains consistent with the Quaker belief in the anonymity of the “priesthood of all believers.” This democratic spirit is exemplified in the horizontal, consensus decisionmaking process of the Occupy movement so similar to the sense of the meeting in Quaker spirituality.

Buffalo Friends have given voice at general assemblies and working group meetings, facilitated social justice teach-ins, and donated food. Some Friends helped to organize and participated in an interfaith celebration at the square. Some Friends have helped to build bridges between “occupiers” and established institutions such as universities, religious communities, nonprofits, and labor unions. These examples of collaboration between Friends and occupiers reveal solidarity in social justice, nonviolence, and commitment to democratic process.

I suggest what we can learn from each other. Friends are well trained in facilitation and sense-of-the-meeting decisionmaking and are civically engaged. Friends have also tapped into the healing power of silence, the Shakti energy of the universe, and have thereby developed an ability to “listen.” Occupiers have a depth of conviction and passion that is always the spark of spiritual evolution and social transformation. I hereby propose a synthesis.

Occupy Wall Street and Buffalo Quakers

Chris Barbera, Buffalo Meeting

I am reluctant to write about the Occupation movement. There are several reasons for this. First, it is something to be experienced rather than gleaned from the abstraction of the written word. Second, no one voice should hold precedence. This is a key to consensus democracy rooted in horizontal rather than vertical leadership. We are all voices, we are all leaders, and we all experience life with equal dignity. Putting these concerns aside for the moment, I’ll write anyway (I have this feeling during Quaker worship when I want to respect the silence but speak anyway).

A week before Occupy Wall Street (OWS) came to Buffalo on a bus tour, the Buffalo Occupation was invaded. Ten people were arrested and property was destroyed. The military apparatus solution of the empire took precedence over the well-meaning but empty words of the city fathers within the “city of good neighbors.” And so Buffalo Occupy was just beginning to pick up the pieces and find out how to recover the seeds trampled underfoot and start anew. The members of OWS were welcomed as a breath of fresh air.

The OWS people possess a depth of conviction and seriousness that harmonized with a revolutionary business-as-usual attitude that shattered any pretensions to self-righteousness. The OWS members embody and advance the cosmopolitan edginess and cultural, political, social, gender, and spiritual diversity of New York City. Perhaps it is fitting that this core of diverse peoples were some of the ones to challenge the hegemonic financial monopoly of Wall Street. It is easy to see how the inner light of each individual is harmonized into a collective of free spirits and free thinkers. The consensus democratic process is the unifying principle. Within this model of social development, each individual is free to be and free to be in solidarity with each other individual or collective of individuals. We are not a melting pot where everyone is assimilated and reduced to a lowest common denominator of consumerist self-gratification. When people are made the same, they are easily enslaved. Diversity advances freedom. And the freedom of the Occupy movement is tied into noncooperation with the economic, social, and political model of Wall Street.

After Quaker worship, and after a short fellowship, we reassembled to listen and to share with the few members of OWS who were our guests. We sat in a circle and listened and spoke. There was no facilitator and no agenda and so the structure was open but fairly well organized. Most people present spoke. On that particular day, we had guests who hailed from Russia and Sweden, OWS people who hailed from New Orleans, Erie, PA, and Brooklyn Monthly Meeting, as well as Buffalo friends from Asia and Africa. Honoring the voices of all people from around the world, and giving each person the freedom to be themselves is part of the solution. This is one of the roots of the paradigm shift to a genuine egalitarian democratic structure advocated and experienced by the Occupy movement.

Later that day, outside of Quaker worship, OWS had a five-hour-long strategy-and-networking meeting with members of the Buffalo community. We spoke about housing and healthcare and building collaborations with grassroots communities. We assessed where we have been and where we are going. First, the Occupy movement captured the imagination of many through resistance and autonomy by occupying and reclaiming public space, drawing the lines between the 99% and the 1% and creating a democratic forum. In solidarity, we began to point out oppressive economic, political and social structures. These structures are beginning to be replaced by the very way we interact with one another, as well as through traditional forms of “protest.” And now we are moving into phase 2.

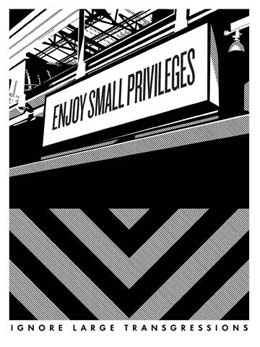

|

| image courtesy of obeygiant.com |

![]()

Participating as a Quaker in Occupy Faith NYC

Tom Rothschild, Brooklyn Meeting

Like bubbles in an overheated stew, concerns over the large and increasing disparities of wealth and income in the US have been growing in our society until, rising to the surface, they burst into the open air last fall in the form of Occupy Wall Street and related “Occupy” movements and organizations.

As a Quaker concerned about these disparities, and their corrosive effects on democratic structures and other social institutions, I felt called to support this new movement, but was unsure what form this support should take. I was perhaps most concerned about the rallying cry of the “99%” versus the “1%.” Certainly this encapsulates well the economic realities that Occupy Wall Street addresses; but at the same time, this has often resulted in a disturbing demonizing of the “1%” that left me uneasy. Additionally, I feel called to participate particularly as a Quaker, and particularly as a part of a larger spiritual community, an interfaith community.

For these reasons, I immediately resonated with the nascent organization Occupy Faith NYC, and I have participated in many of their meetings and activities since last November when I first learned of it. Occupy Faith NYC is a group of clergy and others in faith-based and humanist-ethical-based communities and organizations who wish to support OWS and more broadly the Occupy movement in its commitment to raising issues of economic and social justice, and in particular to support the nonviolent and democratic approach to which OWS has expressed commitment. As a member of our religious Society, which has, as we so often proclaim, abolished the laity, I have felt quite comfortable participating and have been accepted as an equal with those from other traditions where clergy are only those specially ordained or appointed. Occupy Faith NYC is also part of an informal network of Occupy Faith across the US, so I have also had some wonderful opportunities to meet and hear from participants in Occupy Faith groups from other parts of the country.

What follows is my own personal understanding of some of the basic principles of Occupy Faith NYC. There are at this time no formally approved statements of these principles. While the principles have been discussed and generally approved at meetings of the group, acting on a basis of consensus, there is no agreed formalization or minute, such as we would find in a meeting for worship with a concern for business. Furthermore, the membership of the group at the present time is entirely self-selected and amorphous, making such formalization difficult at best. There is some effort under way at present to broaden the group, and perhaps some clearer organization will result from that; but there remain certain tensions, which can be used either creatively or destructively going forward, between keeping the group completely open in membership or stating membership in some more or less clearly defined manner, and between communities, in particular our Quaker community, which are not at all hierarchical, and those which are more or less strongly hierarchical, with different degrees of authority and requirements of obedience embedded in that hierarchy. For these reasons any current statement of principles of Occupy Faith, not just this one, are ultimately personal interpretations. However, with this caveat (and after conferring with one of the organizers of Occupy Faith to confirm my understanding), I believe that what follows does in fact represent points of unity or consensus for the organization at this time.

First of all, Occupy Faith sees itself as an organization of “faith leaders in support of the spirit of Occupy Wall Street.” Expressing our role in this manner means that we are not bound, as an organization, to endorse every statement, position, or action that OWS or OWS participants take or engage in. At a recent meeting, we agreed in particular that as faith leaders we bring compassion for all people. This includes specifically compassion on a personal level for the “1%,” who are still human, no matter how much we may disagree with their economic or political stance, and despite our support for changes in society that would tend to reduce their economic and political power and influence. In this way, Occupy Faith addresses directly my personal concern about demonizing the “1%” and makes me feel easier about it, makes me feel its approach is consonant with my own understanding of our faith and practice. That is not to say we should not resist evil, should not name it, call it out, refuse to cooperate with it. However, I believe that it is through engagement in love and compassion with those seen as “other,” rather than by antagonistic confrontation and personal attack, that Quakers have been most effective in bringing about positive change in the world.

Occupy Faith wishes to base its positions and actions on a moral reframing, a moral vision of a society as a whole. Our ideal is to continue in the prophetic tradition of “speaking Truth to power” in calling for a society of economic justice and democratic process, a society that will refuse to accept poverty in the midst of plenty. As a Quaker, I join in this call and wish to add my voice to this prophetic strain of our own time.

Let Your Life Speak All Day All Week

Cressa Perloff, Brooklyn Meeting

When I was in eighth grade my Social Studies teacher gave us an assignment in which we were to research any issue and write an informative letter (essay) to our representatives. I researched sweatshops. I remember noticing that a different distribution of wealth within a clothing company would enable workers to be paid fairly while keeping clothing prices competitive. A few months later, I received a form letter in the mail letting me know that my senator was concerned about this issue too. My 13-year-old self became aware of my perceived powerlessness.

I feel drawn to the Occupy movement for many reasons. For one, income distribution and fairness have deeply concerned me intuitively for much of my life. The movement speaks to me politically. But perhaps more importantly, I see the movement as a platform for those who are normally quieted, a space to feel affinity with one another and actualize ideas. Also, the Occupy movement offers a kind of alternate society in which individuals can witness and learn from an organizing structure that empowers and listens to them. But that’s just me. The Occupy movement, with its purposeful lack of demands, is open to a great many voices. Many who have felt disenfranchised for so long have responded with anger and scattered passion, which disturbs me. So I asked myself, through what community might I support this movement, and in what capacity? I felt that by participating through the Quaker community I could be part of a group that focuses on grounding passion peacefully.

As a regular attender at Brooklyn Monthly Meeting, I wanted my community to help me find the inner strength I sought to carry on my convictions. I thought that in order to participate wholly, I would need my community’s participation alongside me, not distantly in solidarity, in order to deal with the callous and rash voices I was hearing within the movement. While I knew there was no rushing this degree of action, I felt that much of the slowness was because Friends did not have a sense of the scope of this kind of engagement, of where we are in our own history. So I embarked on writing an extensive article to provide such a context.1

In my research, I found that Quakers have often had society’s organizing structures in mind. At first, Friends communally challenged the status quo but were not purposefully confrontational. As persecution pushed them off their farms and into industry, Quaker business thrived by practicing fair business and networking. By the time the Quaker John Bellers proposed in 1695 that redistribution of resources could alleviate poverty, Quakers had developed a sincere disdain for larger society’s sense of luxury. John Woolman’s traveling ministries led to group action regarding slavery only after many Meetings in the northeastern United States came to unity on the issue. But Quietism and the Industrial Revolution spurred a period of Quaker history in which individuals were the main purveyors of social change, whether it be prison reform, founding colleges, or the women’s suffrage movement. In the early 1900s, after Benjamin Seebohm Rowntree proposed that poverty was a systemic issue of wages and not a sign of moral depravity, Quakers developed the committee structure and AFSC, among other organizations—communal responses to the acknowledgement that societal problems are the result of economic systems. In the mid-1900s, the Movement for a New Society branched from “service” to “activism” and powerfully transformed social movements with its theories and resources on nonviolent direct action. Their work has provided a large foundation for social movements in America since, including Occupy Wall Street.2

So, as Quakers have cycled through community and individual action, and as we have very slowly come to denounce political manifestations of depravity, it seems only natural to me that we are primed to come out and respond communally to systemic and corporate offenses to our deeply rooted sensibilities. Our issues are not new, but we are confused and afraid of facing the injustices we care about. While slavery was an obviously moral issue, today’s issues are muddled by politics, which I believe imbues Quaker communities with a fear of unjustifiably offending our own members. But it is justifiable. My rather audacious query is this: Is our fear of offending each other a kind of empathetic transference of our own fear of being called out for not letting our lives speak, due to the confusion of complex global issues and manipulative politics? Let us be empowered—not debilitated—by a trait noted by the Nobel Prize organization in their history of the Quaker service organizations that won the Peace Prize in 1947:

In all of this service, Quakers have been anxious to stress that the work they have felt able to undertake has been of modest proportion and that they have been more concerned with personal relationships than with large-scale operations. They have stressed, too, that their service springs directly from the personal concerns and insights of individuals, tested by the corporate guidance and judgment of the group....3

This concern for relationships and individuals could instead inspire the kind of guidance that Occupy is basically begging for right now. At the time of this writing in mid-February, responses to Chris Hedges’ belligerent denouncement of “black blocs”4 have inspired deep reflection within the movement on how it defines nonviolence and the reaction (read: level of compassion) it should have toward participants who loosely define or disregard it. A coworker of mine who had participated in WTO protests told me recently that she is not involved in Occupy out of fear of being bashed in the head because she does not know how to keep herself from getting destructive toward “evil corporations” and their proponents. But many are not so self-aware or cautious.5 To me, her example is the epitome of our calling: that a person’s deeply held convictions could lead to violence that begets violence. But we could be a part of stopping that cycle.

Regardless of political affiliation, Friends have infinitely much to offer in the way of transforming anger into what a Quaker friend of mine calls “fierce love.” With our historically and spiritually indomitable belief in the ability of humans to call out to the Light in others, and with our clarity regarding linking intent and action, it is important for us to lend our voices to this movement. At the very least, we might reduce violence. At the most, we can occupy the world’s dialogue with the integrity of Love.

1. That piece will mostly likely be finished by the publishing of this piece, but it is too long to publish in this issue.

2. Most of this historical information was obtained via http://throughtheflamingsword.wordpress.com, a blog by Steven Davison, who is authoring a book on Quakers and Capitalism.

3. www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1947/friends-council.html

4. This article contains some inaccurate information and should be read as a sign of the times: www.truthdig.com/report/item/the_cancer_of_occupy_20120206/.

5. As an awesome aside, she channels this constructively by teaching self-defense classes to homeless queer youth.

Ministering to the Military

Joyce Ketterer, Brooklyn Meeting

When I think of places where my commitment to look to that of God in everyone would be most tested my mind first goes to organizations like jails, the military, and Fortune 500 board rooms. Of course, these are the places where such a skill is most needed, where transformative experiences will be strongest, and where the possibility for experience of the divine is most life changing. I would like to tell a story of such an experience in my life with the military. When, in mid-July of 2011, I gathered my courage and made a phone call to the air chaplain recruiters’ office I could not have known that the man who answered, Chaplain Gunn, would prove to be a great ally. Each of us could easily have approached the conversation as adversaries. I could have assumed that it was his job to frustrate the applications of folks exactly like me and he could have assumed that I wanted to undermine the mission of the air force. Instead what I found was proof that there is “good there” in a person who believes in both the Rapture and the need for humanistic spiritual nurture within military ranks.

I had been sitting for some time with the possibility that I was called to engage with the military on their own terms, to provide a liberal theological ministry within the chaplaincy, and in so doing to help Friends to reconceptualize our relationship to the military. As a lifelong liberal Quaker, a nontheist, and the daughter of lesbians, I knew that any application to became a commissioned military officer would not be easy and I specifically chose the air force because of their reputation for having the greatest problems among the military branches with religious pluralism.

|

To quote my mother, “The only reason not to choose the Air Force is if you actually want to get in.” She was thinking of recent news stories about evangelical efforts in the Air Force Academy and punishments by faculty (mostly commissioned officers) of students who did not share their conservative religious views. The same week I first spoke to Chaplain Gunn, a story broke about chaplaincy involvement in required training for bombers who would be the ones called upon to implement the use of nuclear weapons. I can only credit grace for implanting in me sadness instead of anger and the desire to help in place of the desire to condemn. There are already exceptional watchdog groups, and what is needed now is for some of us help them find the way—hand in hand.

Friends often talk about “looking to that of God in everyone” but I don’t think that we speak enough about what that means. Friends often find fellowship with those who have left the military, those who want to leave, those who have retired and reflected on what was not good in their military careers, and those who are physically or emotionally wounded by military service. That’s not enough. For me, looking to that of God in the military starts with respecting the leadings of individuals serving actively. Many believe that they have a calling to serve and protect. They believe that military action can sometimes be the only answer to a crisis caused either by humans or by nature, and I am not prepared to say that they are wrong. Even a military force that never commits atrocities will test the limits of its ranks and require spiritual nurture. I believe that an armed force that reflects the pluralism of our nation requires us to be a part of providing support, because no one else can offer our perspective.

Let’s stop for a moment and think only about the folks who are suffering now, people who are marginalized by conservative religious culture and abandoned by liberals because of their vocational choices. Atheists, agnostics, nontheists, folks with religious affiliations other than the big three, LGBT people, and others often lack institutional support in the military. I wanted to be a chaplain because I wanted to support those people and because I wanted to be part of a cultural shift in both the military and Quakerism that would hopefully lead to greater unity.

My application went fast. Chaplain Gunn and I realized in our first conversation that that we had very little time. The military accepts relatively few chaplains each year, and because I come from a background from which I would gain little direct ministerial experience, my best shot was to become chaplain candidate—a program for which the deadline is the applicant’s 35th birthday; mine would be January 4, 2012. We began in earnest almost immediately. I applied for and was accepted to Earlham School of Religion; we verified that there is no liberal Quaker body certified by the Department of Defense (DOD) to provide the essential chaplain endorsement and that the evangelical “Friends Church” body which was registered with the DOD would have nothing to do with me because I would not agree to their statement of faith; I searched for some other body that could help and found the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship. We even went so far as to fill out a form that described my schedule for the next three summers and put in a request for my top three chaplain-shadowing assignments. In the midst of all this another recruiter had me filling out medical forms, which turned out to be our undoing. Under the time constraint I have too many red flags on my medical history—things like being dyslexic and having gone to a psychotherapist. I could have kept going. I could have stayed in seminary and acquired debt for a long-shot application to the regular chaplain corps. Together with my clearness committee I determined that this had been my leadings test and that I was done. With a heavy heart, I told Chaplain Gunn (now Paul) that I would not continue. I am still not certain which of us was more disappointed.

At the point that I felt clear to reach out to the air force I was so deeply in my own mind-set of engagement and compassion that I was shocked to learn that many assumed I might see my purpose as that of an evangelist for pacifism. Chaplain Gunn asked me gently, mostly as a matter of form, but many Friends were equally shocked by my response that it would be unethical to embark on such a mission after agreeing to the oath that would allow me to join. There will always be a role for Friends in speaking out against violence, and I am suggesting a second role that in no way undermines that effort. It is time that we take back our seats at the national table and claim our power. For too long we have allowed others to define the military in terms that are to us negative and have, by standing on the sidelines and hurling blame, effectively removed ourselves from an important aspect of our national community.

Some seem to think that disowning the military can accomplish something positive. I think that we can see now that it only does the opposite. More and more, the military community of this country is like its own separate nation, a sad fact that certainly wasn’t true 50 years ago. With less and less overlap we are increasingly able to “other” each other. We call them bullies and they call us cowards and in so doing we sow seeds that could one day bear deadly fruit. In the coming years this, my yearly meeting, will be hearing more from me about my calling to offer liberal spiritual support within military ranks. I hope we will follow the examples of the Unitarian Universalists and United Church of Christ and do as we have done in order to enable our prison work. I would like for us to seriously consider that we might be able to reach clarity to provide a DOD endorsement office for Friends who wish to serve as chaplains.

Those serving in the military have spiritual needs. Most liberal faith communities have pacifist tendencies, and so we who are among the leaders in the Christian pacifist tradition cannot disown the military with the knowledge that enough other liberals will step in to serve the spiritual needs of service people. Sure in the knowledge that a standing military is a fait accompli, I see no other option than to ensure that the military community is not ceded to those religious folk who would teach a theology of hate.

Out of My Comfort Zone: VA Medical Center

Astuti Bijlefeld, Central Finger Lakes Meeting

After more than 10 years as a hospital chaplain and generally at ease with the great diversity of people encountered in hospital settings, I knew there were some people I still avoided. Never having had any exposure to military life, to its traditions, expectations, language, or values, I felt there was no ministry I could offer to veterans. But I also carried a growing sense of unease. I began to pay attention to the obituaries of men about my age and, when the death was “unexpected,” noticed that the life story often included combat time served. These Vietnam-era veterans came to be a continual reminder that so many men and women still carry the invisible wounds of that time. There are some 7.5 million Vietnam-era veterans among us as the number of younger veterans keeps growing. In the first days of the Iraq invasion in 2003, a WWII veteran told me why his hospital room was silent, the television off: images of another generation of young people being sent to war were too painful for him. Now, eight years later and with total of more than two million deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, the injuries of war affect that many more veterans and those around them.

Some years ago I knew it was time to move out of my comfort zone, both personally and professionally. The thought kept recurring that there would be few places more out of my zone than a Veterans Administration (VA) Medical Center. At first the thought was so unlikely to me that I hesitated to share it with Friends and instead looked for confirmation from other sources that I could offer meaningful spiritual care in this setting. Thinking about the possibility, much of my training for ministry that had gone before started to look like preparation for this challenge. About that time, a man who had observed my emergency room interaction with his irate family member asked me whether I had served in the military. His question came as a confirmation that my ministry would be accepted among veterans. I went on to inquire at two area VA medical centers and was warmly welcomed by the chaplains there. And when I finally brought my hope to Central Finger Lakes Friends, it was received with the same loving care and encouragement that has carried my chaplaincy work all along. They affirmed my hope that work toward healing the spiritual wounds of war will be work for peace.

The Meeting’s care committee supported me through the lengthy application process and the waiting. Central Finger Lakes Friends Meeting had already approved a minute of endorsement for my chaplain’s work that met national certification requirements while also testifying to the ministry of all believers. This minute was endorsed by Farmington-Scipio Regional Meeting and at Spring Sessions in 2009 by NYYM. There was no precedent in the VA for a chaplain endorsed by an unprogrammed meeting, but after three years and much paperwork, I was able to start as per diem VA chaplain this winter.

At the VA and from a VA chaplain I first heard the words of Pope John Paul II, who called war “a catastrophic failure of man’s inability to resolve conflict.” While Friends continue their work to resolve conflicts peaceably, there remains the immediate need for care and compassion for those directly affected by war. As chaplain at the VA, I am learning to offer that care to veterans, on their terrain and on their terms.

Blaming has no positive effect at all, nor does trying to persuade using reason and argument. That is my experience. No blame, no reasoning, no argument, just understanding. If you understand, and you show that you understand, you can love, and the situation will change. —Thich Nhat Hanh

How Michele Bachmann Taught Me to Pray

Chris Nugent, Dover-Randolph Meeting

For most of that summer I screamed myself hoarse seemingly every time I turned on the television. Always there was that hateful woman spewing her fears and lies about gay people and using her position as congressperson to try to hold us down. How I loathed her. I wished Michelle Bachmann was truly beneath my contempt so I wouldn’t have to think about her ever again.

|

I had been a Friend for several years at this point, but spiritual concerns were entirely absent from my response to Michele Bachmann. Unadulterated rage was all I could muster. One evening as I was screaming at the television, thinking that perhaps I should invest in throat lozenges, it occurred to me that my behavior might not be the most healthy or productive. It began to dawn on me that I was letting a total stranger compromise my emotional and psychological well-being. I didn’t know what to do with this realization, so I sat with it, uncomfortably. At least it beat losing my voice every time I dared turn on the television.

So I started to think about Michele Bachmann when she wasn’t on TV. The thought of her very existence made me angry still. But I wasn’t screaming. The experiment was proving to have real, albeit limited success. I resigned myself to a state of chronic barely controlled anger.

I didn’t actively bring this concern to meeting, I didn’t pray about it, I didn’t lay my rage under Spirit’s comforting wings. This seemed like something between me and Michelle Bachmann, or a purely internal issue within myself. I certainly was not expecting the prompting, when I encountered her on TV yet again, to pray for Michele Bachmann. I was taken aback for a moment, but quickly saw the wisdom in this leading. I offered the same prayer for her that I make for myself and everyone I pray for: Grant us joy and strength and peace. I didn’t choke on the words or the sentiment, but clearly this was not enough. Her face was still on the screen; I pictured her whole family, offering them joy and strength and peace. I didn’t really notice any change in myself until I prayed for her dog (to this day I don’t even know if she has a pet). And so, for weeks after I spent a lot of time praying for the Bachmann’s extended family, always with a special prayer for the dog.

Gradually, rage gave way to pity. How hard it must be to carry so much venom that it can only come out as attacks on a convenient scapegoat. I considered writing Michele Bachmann a letter telling her a gay man was praying for her, not for her conversion, but for her to experience genuine joy, unbreakable strength, and bottomless peace. My trust was that if God were to grant her these boons she would be utterly transformed in ways I couldn’t begin to imagine, which would be profoundly positive. I did pray over writing such a letter, but no guidance was forthcoming, so I let it go. I don’t know if Michele Bachmann has had such joy and strength and peace. I pray she has, but my job is not to change her, but to be faithful to God myself.

Wouldn’t that make a satisfying conclusion to this story? But I have difficulty with lessons from the Spirit. A year or so later I attended Catholic mass with my mother in remembrance of my father’s anniversary. There is much to be grateful for in my Catholic background, but there is good reason I left the church. The priest yielded his time for the homily to a laywoman from the diocese who inveighed against marriage equality, using the same vile arguments and analogies that sent me over the edge with Michelle Bachmann. I wanted to scream or at least storm out of the church, but that would have accomplished nothing, except antagonize my mother. So I sat and fumed. Ultimately I did form a prayer for this woman, but my mother’s silent presence at my side complicated matters for me.

Mom’s gotten a lot better, but she can hardly be called supportive of my sexual identity. Love, anger, disappointment, concern, pity, and understanding tumble in unpredictable patterns about my prayers for her joy and strength and peace. So, I am thankful to Michelle Bachmann for making me aware of the spiritual power of this conundrum. The likelihood of my prayers’ changing anyone else directly is slim to none. But the more I hold our common spiritual needs in prayer the better prepared I am to follow the path God sets for me.

There is a fine line between wrong and visionary. Unfortunately, you have to be a visionary to see it.

—The Big Bang Theory, season 3, episode 4

The Place in Between

Chris Rossi, Hamilton Meeting

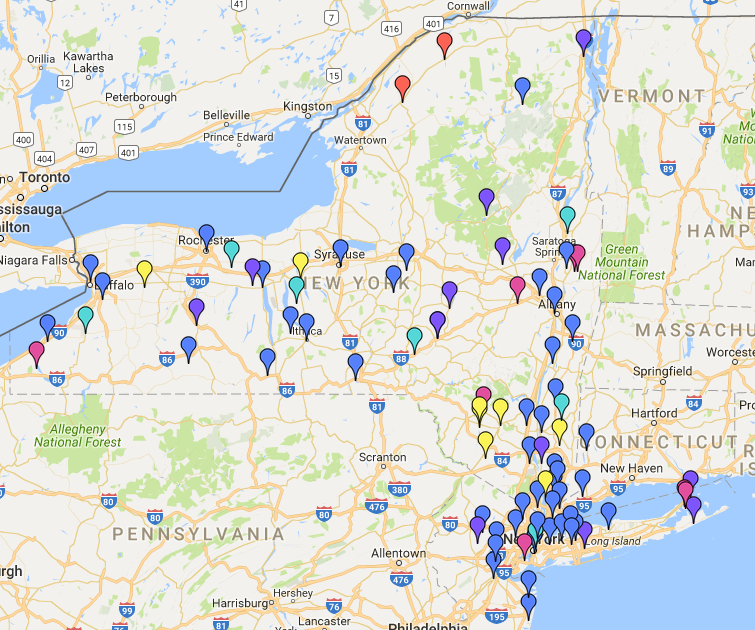

I have been involved in struggles for environmental justice before. In fact, I was an organizer in a movement against a proposed 200-mile-long 400,000-volt power line meant to go through upstate New York communities from Utica down to Orange County. We organized locally and worked with groups all along the 200-mile proposed path, and we won. New York Regional Interconnect (NYRI) retracted their application with the PSC and we happily gave up our three-year-long struggle and went back to our lives.

That is, until unconventional gas development, otherwise known as hydrofracking, came along. New York State has experienced gas development in the past, but this new technology presents a whole different challenge. The power line presented no benefit to anyone in its path. A fairly clear issue for upstate New Yorkers, we were all united against the NYRI corporation. They were easy to oppose and depersonalize, as they were a faceless corporation from another country. Not so with hydrofracking. Yes, there are corporations and politicians on both sides of the debate, but with this issue much of the argument is among friends and neighbors.

Passion runs high when we try to discuss the merits and hazards of hydrofracking. We talk about pollution and land rights. The need for income for impoverished farmers versus the fear of losing our clean water and compromising our health. I have heard fractivists compare this issue to abolition and pro-development folks invoke the spirit of the constitution. The concept of middle ground is not well received and there is a lot of “You’re either for us or against us!”

| …the biggest threat from hydrofracking might be the hazard of fracturing our communities with long-term enmity. |

How do we talk about this fraught issue without losing ourselves and our relationship to community? A friend of mine says the biggest threat from hydrofracking might be the hazard of fracturing our communities with long-term enmity. To avert that end I have been involved in an effort to foster dialogue around the issue. Citizens for Safe Energy was formed to find common cause within our community around natural-resources issues. Instead of focusing on what we disagree on, we have concentrated on what we can agree on—the preservation of the water, the air, our homes, and the community we hold dear. This approach involves holding people on all sides of the issue in the light of respect and honoring the sincerity and passion behind their views. It requires public meetings that are safe places to speak about hydrofracking without fear of being shut down because of your perspective or ideas.

We have held educational events and a roundtable workshop, bringing together people from all sides of the issue to talk about concerns we share in common. Attendees have expressed thanks for having a place for rational dialogue and balanced information. We have been put down by some for not being committed enough to either side of the discussion, but that is right where we think we may do the most good.

Occupying a space in the middle of a very heated issue is not a comfortable place to be, and it can be very frustrating. Sometimes I look back on the Stop NYRI campaign and am envious of how clearly defined that struggle seemed to be. But I am now convinced that debates over hydrofracking, or power lines, or windmills, or nuclear energy, or the next energy source of choice, will always be with us. To negotiate these issues as a whole community we need to relate to those we don’t agree with not as the “other” but as our neighbor. As Friends this is what we are called to do. In that regard, working from a center of respect, true listening, and fellowship to create inclusive community dialogue may be one of our most important roles.

Why I Am a Fracking Abolitionist

Sandra Steingraber, Ithaca Meeting

I have no idea of submitting tamely to injustice inflicted either on me or on the slave. I will oppose it with all the moral powers with which I am endowed. I am no advocate of passivity. —Lucretia Mott

I am a biologist who researches and writes about environmental contamination. I am also a Quaker “by convincement.”

On September 11, 2001, I was the mother of newborn son, and it was the simultaneous experience of birth and war that led me to the Friends community. Occasionally, I arrive to meeting for worship right from the airport, having just spoken in a toxic community somewhere. As I worship, I sometimes imagine the Quakers before me who worked as abolitionists with the Underground Railroad or who struggled for women’s rights or for nuclear disarmament. Quaker history lets me know myself as one small link in a very long chain of witnesses for human rights. Because environmental destruction harms children and begets violence, working to protect the abiding ecology of the planet seems to me a consistent part of our larger commitment to peace.

|

| photo by Tim Ruggiero |

We Quakers are called to seek out the sacred within the transactions of ordinary life. For me, this is the easiest of our spiritual tasks. I am joyfully aware that, in any given moment, we each enjoy an exquisite communion with creation, as molecules of our environment stream through us, break apart, rearrange themselves, and become our bodies and our blood. Our children are made of air, water, and food. The plankton stocks that make oxygen, the bedrock that holds groundwater, the pollinating bees that turn flowers into fruit: these are blessings (or what biology calls “ecosystem services”). Chemical poisons should not trespass here.

Two other elements of the environmental crisis are spiritually more difficult. The first is the paralyzing passivity that prevents otherwise concerned people from acting. The second is conflict with those people who take stances that are “clearly inimical to our sense of the Light.”

Collective despair, in my experience, is the biggest obstacle to environmental justice. Little wonder. Our problems are overwhelming and entrenched: our economy is now ruinously dependent on fossil fuels in the same way that, in the 1830s, it was ruinously dependent on slave labor. And both are homicidal abominations.

Fossil fuels, when burned, are destabilizing the planet’s climate system in ways that threaten the world’s plankton stocks and pollination systems, on which human life depend. The World Health Organization tells us that climate change is already killing people around the world, and its primary victims are children.

Fossil fuels, when used as feedstocks for the manufacture of petrochemicals, create toxic chemicals. (The US petroleum industry accounts for one-quarter of toxic pollutants released each year in North America.) These also kill people, including children. The best science shows us that we could entirely divorce our economy from fossil fuels—just as we have divorced it from unpaid slave labor—and embrace renewables to meet all of our needs…if we were willing to reduce our nation’s energy consumption by half. But what often prevents people from forceful insistence on reaching this goal is their own despair. They give up hope before they’ve even started.

A commitment to faith in action and love in action can be powerful antidotes to what psychologists called “well-informed futility syndrome.” In this, I’m particularly inspired by antifracking activist Tim DeChristopher.

I was at the courthouse in Salt Lake City, Utah, when Tim DeChristopher was sentenced to prison for disrupting the auction of public lands for gas and oil drilling. Tim had participated in the auction as a bidder and indeed won many bids—but without the millions of dollars in his bank account needed to make the purchase. The publicity surrounding his actions served as a spotlight, ultimately revealing that the auctioning of these lands was illegal in the first place. The winning bids were declared null and void. So his actions really did stop the drilling.

But that outcome did not prevent Tim from being charged with fraud. On July 26, 2011, he was sentenced to two years in federal prison. In a most extraordinary moment, Tim said to the judge, “This is what love looks like.”

Tim’s words have helped me during confrontations with my own opponents. When I debate oil and gas industry representatives—in town hall meetings, on television, on college campuses—I do not speak from a place of compromise. Sometimes I am very fierce. But I always want the ferocity in my voice to be an expression of love and intention to protect what is sacred. I want my words to bear witness to what poet John Knoepple wrote in his poem “Confluence”:

this world in peace

this laced temple of darkening colors

it could not have been made for shambles

During debates and confrontations over fracking, I never try to change anyone’s mind. I do try to open a rhetorical space in for change to occur. I have set a glass jar of my own drinking water before a gas industry representative and said, “This water is for you. It is drawn from an aquifer located downhill from fields leased to your company for fracking. In this water is the blood plasma of my children, their cerebral spinal fluid, their tears, the steam of their breathe on a snowy day.” Marching in procession through the New York statehouse with farmers, millers, and bakers, I’ve delivered a hundred loaves of artisanal bread to the governor’s office. We chanted, “break bread, not shale!” and built a mighty bread mound in his outer chambers.

****

There is no other way to say it. The woods of William Penn are being shredded by fracking. The bedrock below the woods of William Penn is being blown apart by fracking. The people who live in the woods of William Penn are losing their ecological life support system in order to extract a form of fossilized carbon, methane, that is a potent greenhouse gas. And some of those people are being poisoned. How will Quakers bear witness? How will we resist—in a spirit that takes away the occasion of all war—the “invasion of the shale army,” which is how the gas industry, with no irony, describes its own actions?

|

| Sue Heavenrich, Marcellus Effect http://marcelluseffect.blogspot.com/ |

The Marcellus shale of Pennsylvania—and New York, Ohio, West Virginia, and Maryland—is an oceanic graveyard. Those bubbles of methane trapped inside represent the bodies of marine animals, sea lilies, and squids that died 400 million years ago. But the Marcellus shale is also alive. It’s an ecosystem, teeming with colonies of relic organisms—bacteria and archaea—that microgeologists call deep life. Deep life organisms may make up more than half of the total biomass on Earth. They play a role in the carbon cycle and may therefore play a role in climate stability. To get gas out of the shale, you have to kill them. That’s one reason that fracking fluid is so toxic. It contains biocides.

Fracking risks public health injury at every step. Open-pit mining of frack sand in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Illinois is sending silica dust—a lung carcinogen—into the air of rural communities. The siting of drill pads fragments habitats, compresses soil, and contributes to sedimentation of surface waters. Chlorinating water full of sediment generates trihalomethanes (disinfection byproducts), which function as bladder and colon carcinogens. Meanwhile, the deep-well injection of wastewater is linked to earthquakes. The drill cuttings contain radium-226, which has a half-life of 1,600 years. Fracking is invariably accompanied by increases in smog, soot, and criteria air pollutants. These are linked to asthma, cancer, stroke, heart attack, premature birth, and premature death.

Just as Quaker abolitionists sought to ban the institution of slavery rather than reform or improve upon it, I seek to abolish fracking. My least favorite word from the world of fracking is mitigate. That word actually has two meanings. It’s usually used in its first sense: “to make less bad.” The other meaning of mitigate is “to partly excuse a crime.”

The tools of mitigation, as they apply to fracking, do not make harmful chemicals disappear. They simply delay their release—or transfer them elsewhere. If we disallow open pits for wastewater, less carcinogenic benzene evaporates into the air—but more benzene is contained in the wastewater that is buried, say, via deep well injection in Ohio.

Similarly, if we insist on recycling the fracking wastewater and reusing it to frack new wells, we create additional toxic pollution: Too briny and toxic to use as is, the wastewater requires filtration or distillation, which, in turn, requires massive amounts of energy—thus generating more air pollution and adding to the carbon footprint of gas—and the leftover sludge still has to be buried somewhere, but now the contaminants and radioactivity are even more concentrated. The more we insist on triple casings around well bores, the longer we delay their eventual corrosion and leakage. So instead of exposing our own kids to carcinogens, we expose our grandchildren. According to data gathered by biochemist Ron Bishop of SUNY Oneonta, half of all gas well casings leak within fifteen years. Repeatedly exposed to corrosive fluids on the inside and not bonded to the surrounding rock on the outside, wells can even continue to leak years after they are inactivated and plugged.

Here, scientific evidence and Quaker practice align. With love and resolve, we can say: Fracking is wrong. Fracking is unmitigatable. Sooner or later, steel and concrete disintegrate. Sooner or later, gas wells open portals of contamination. Doing fracking “right” simply means building time bombs with longer fuses. There are no places and no children that we are willing to sacrifice. This needs to stop.

A video of Sandra addressing an antifracking rally in Albany can be seen at http://bit.ly/wEcFIn.

![]()

|

| photo by Michael Forster Rothbart |

| Michael Forster Rothbart is a member of Ann Arbor (MI) Meeting and currently attends Butternuts Meeting in Oneonta, NY. As a Quaker photojournalist he uses his camera to witness, among other things, how the issue of fracking is tearing apart communities as it stands to change them forever. This bridge crosses the Upper Delaware River at Narrowsburg, NY. The Upper Delaware Scenic and Recreational River stretches 73.4 miles along the New York–Pennsylvania border and is a nationally significant fishing, boating, and recreational destination. In addition, roughly 58 percent of the land area of New York City’s West-of-Hudson watershed is within the Basin. Fracking poses numerous risks to the area. |

![]()

From Despair to Empowerment

Christopher Sammond, Poplar Ridge Meeting

Over 60% of my county is leased for gas production. There are another 100,000+ acres held by a landowners coalition, ready to be leased, once they can strike a better deal with a gas company. The other five counties around me are similarly poised for massive gas drilling and production. One Friend I know lives amid leased land on three sides of their house. Fracking, short for high volume, slick-water horizontal hydrofracturing, is all around us.

When my wife, Barbara, and I moved to Cortland County two and a half years ago, we noticed lawn signs with the “interdict” symbol, a circle with a diagonal line drawn through it, and the word fracking underneath that. We didn’t know what it meant, but gradually, we have learned.

The land around us is a series of ridges and valleys, carved out of the shale over millennia by persistent rain and snow, breathed into the atmosphere above us by the Great Lakes to our west. The landscape is covered with woods and farms, dotted with small to medium-sized towns. It is an incredibly beautiful place to live.

Barbara and I have planted fruit trees and blueberry and raspberry bushes, put in an asparagus patch, fixed the breach in the pond, reclaimed the garden. We intend to stay here awhile. We are putting down roots. So while we have not been living here long, the specter of fracking seemed to threaten that dream of making a home here.

|

| photo by Frank Finan, Hopbottom, PA |

In my monthly meeting, two different Friends spoke passionately about the coming degradation of the landscape, and passed around literature. I read that, and then went to Web sites explaining fracking. At first, I thought that this simply could not be as insane and pernicious a practice as its detractors were painting it out to be. You’d have to be nuts to do this, I thought. So I tried to keep an open mind, and not be too alarmist, to hear the arguments on the other side. Yet as I read more and more I opened to the truth that not only was it as bad as I had thought, but it was much worse: very heavy truck traffic (1,530,000 round trips in my county alone) filling our valleys with diesel exhaust and shattering the quiet; the screaming of the fracking compressors, loud as a jet engine taking off; methane released to the atmosphere making fracking as bad a contributor to global warming as dirty coal; vast sums of money being offered landowners for leasing; and the inevitable destruction of our groundwater, the source of all life. That hit me hardest. We have the best tasting well water I have ever known. The majority of homeowners in the six counties around me, and all of our thriving agriculture, is dependent upon this water. Water is life. And I learned that the containment of carcinogenic, radioactive “backflow” from the wells would inevitably, over time, ruin that water. Imagining six counties of ruined groundwater took me to a place of deep grief and despair.

I began to get more active. I went with 450 other citizens to Albany to lobby our representatives. I read more and more. Yet the more I learned about just how bad this could be, and the more I became aware of public opinion shaped by slick deceptive advertisements from the gas companies, the more I witnessed politicians whose reelection campaigns had received generous contributions from the gas industry standing in the way of a reasoned examination of the facts, the more I heard about town boards, made up of landowners who had leases with the gas companies, subverting a democratic practice at a local level, the more I became overwhelmed, bitter, and despondent. I was overcome by grief for this land, and despair over stopping its ruination for the shallow benefit of short-term corporate profit.

Looking back, I see that despair made up of several components: a sense of being victimized by forces beyond any power to influence them, an experience of evil masquerading itself as good, and powerlessness to effect any change in the situation. Thus encountering “the Powers and Principalities” and having no sense of how to respond to them, I was thrown off my center in God and, lacking that center, bought into the illusion of the ultimate power of those Powers and the tools they use: money, human greed and selfishness, corruption, abuse of power, attachment to the status quo.

Then I went to a hearing in Ithaca, where people were offering legal testimony to the Department of Environmental Conservation on the draft environmental impact statement being developed to assess fracking’s impact on the region. Each person was allowed three minutes, and their testimony was both videotaped and recorded by a stenographer. They spoke from their backgrounds in water quality, agriculture, tourism, the secondary-mortgage market, economics, biology, mining engineering, health, air quality, and more. I was blown away by so many powerful, articulate, informed, passionate, and resolute people. Steeped in an atmosphere of “We can do this! We can and must stop this! We will not roll over and let this happen!” I began to regain heart. Their powerful energy of “we can!” was catching, and I left knowing that we would not allow this to be done to the area we love. It might happen despite our best efforts, but we would not be passive victims in the process. The illusion of the Powers and Principalities, that they are all-powerful and there is no recourse against them, was broken.

And that is where this issue touches my spiritual experience as a Quaker, where powerlessness, despondency, and bitter outrage at the perpetrators of environmental degradation can turn to a sense of deep empowerment in God, compassion for our adversaries, and the energy to stand fast. I have crossed back and forth over the line between these two states several times since that hearing, and I am coming to understand just how important that difference in spiritual condition is when confronting systemic evil. It is crucial.

At the height of apartheid, when any hope of ending that abomination was a pipe dream, and all power seemed to be with the white government of South Africa, Desmond Tutu met with F. W. de Klerk, its president, and told him “It’s not too late to join the winning side.” He spoke with utter confidence, inviting him with warmth and compassion. To those who would destroy our water and our air for short-term economic gain, I would say, “It’s not too late to join the winning side.”

There is no evil in this world that has not a little spark of good. If a person only tried to find the spark of good, he could find it. But if a person seeks to find a little spark of evil in every good, he can do that also.…There has never been anyone in history about whom somebody has not spoken evil.…

Every soul has an inclination to admire beauty, to seek for beauty, to love beauty, and to develop beauty.

—Hazrat Inayat Khan

Opening Dialogue

Claire Howard, Poplar Ridge Meeting

I appreciate Spark’s invitation to express how, as an antihydrofracking activist, I keep my own center in the Light as I work against the system that advocates the destruction of our environment (and the living creatures in that environment). How do I keep from vilifying as “the other” those whose ideas and policies I oppose with all my heart? It is a wonderful question, and a helpful question. Because pointing my finger at someone like the CEO of a gas corporation and calling him evil is not my intention. I have just finished reading Ruth Plimpton’s biography of Mary Dyer, the Quaker who in 1660 was hanged in the Boston Commons for her religious beliefs and practices. It is as easy to point to Governor Endicott, who ordered her death, as “the other” as it is to point to Governor Cuomo for his reluctance to protect New York State from the environmental destruction of horizontal hydrofracking. My intention as an activist is to (1) express my opinions and exercise my democratic rights, (2) call attention to what I consider to be the disastrous direction in which we are heading, and (3) open dialogue and effect change. As I write this I am contemplating civil disobedience to amplify my intentions.

As I see it, the Occupy Movement and the Antifracking Movement are very similar. Both intend to bring to light the power and wealth discrepancies in our country; the 1% v. the 99%, if you will. Both grow out of injustice, inequality, and a democracy turned oligarchy. It is easy to become incensed, inflamed, indignant, angry, and self-righteous about these things! But I am reminded of a quote from Logan Pearsall Smith: “To suppose, as we all suppose, that we could be rich and not behave as the rich behave, is like supposing that we could drink all day and stay sober.” Or, “There but for the grace of God go I!”

At Christmastime our hydro-fracking committee had a table in downtown Skaneateles in the middle of the Dickens Christmas festivities. We had brochures, petitions to sign, postcards to send to Cuomo, buttons, and stickers. I remember one well-dressed young man from Pennsylvania with whom my coworker engaged in a rather contentious conversation; he owned land leased to a gas company and was crowing about the $80,000 per month he was receiving in royalties. I edged toward him and made eye contact, putting my hand lightly on his arm. I had a mental image of what could truly be happening to his life and felt sorry for him. “How is your water down there?” I asked. “Oh not a problem! Culligan’s water is great!” That meant pollution had already happened and his water was being trucked in. “But what will your children and grandchildren do for water?” I asked. “Culligan’s will be good enough for them, too,” he responded. I felt a heaviness and a sadness for him and for his neighbors, and indeed for us all. This poor rich man, so cocky and sure, yet so unaware of what was to come. I shook his hand and wished him well. He didn’t want a brochure.

|

| used by permission of Marcellus Effect blog |

A week ago I went to Albany on Antifrack Action Day on a bus with lots of other activists. We were to attend a rally and visit our representatives at the Capitol My group of eight or nine visited Senator DeFrancisco, and Assembly members Pretlow and Magnarelli’s offices. We did not see these powerful men, just their aides and in one case an office manager. That was disappointing, but the aides did their best to appear well groomed, proper, and stoic. It was all quite formal and intimidating at first, but we did our best to make personal appeals and break down the barriers that seemed to be in place in these offices. The aides were so young. One admitted to jumping into Skaneateles Lake after graduation, a local tradition, so we all realized he was a hometown boy! Suddenly the conversation was less guarded and more relaxed and personal. One aide was a lovely African American woman, ripe with an unborn child, who knew nothing about fracking. We of course gave her an avalanche of information, more than anyone could possibly take in first time around, and we appealed to her as parents and grandparents who were concerned for the future of our own children as well as her child’s future. She understood us very well, and she promised to relay our messages and deliver the printed matter we had brought. That was a valuable personal exchange, but just not with the person we had come to see.

These are all examples of interpersonal interactions where “the other” did not exist. That’s what made the experiences so powerful for me. I pray that I can continue my efforts to bring justice and equality to our world in a way that will preserve our precious environment as well as our sense of oneness. Mary Dyer’s words echo in my mind: “My life not availeth me in comparison to the liberty of the truth.”

![]()

Quaker Activism Continues in May Spark!

We received an overwhelming response for our request for articles for this issue of Spark. Therefore, we will feature even more articles on spiritually centered Quaker activism in the May issue. Keep those articles coming! To submit, send articles to the editor, Paul Busby, paul [at] nyym.org, and to the issue’s coordinator, Christopher Sammond, nyym.gensec [at] gmail.com, before April 10, 2012.

![]()

|

Around Our Yearly Meeting

Albany Friends are in the middle of a Quaker Quest (QQ) program, which began in January 2012 and will end March 18. Selected topics of the six scheduled public sessions are Quaker Silent Worship, Quakers as Peacemakers, and Quakers & Continuing Revelation. Clerk Betsy Voss credits the success of the program thus far to careful preparation by the Meeting including training by FGC and a retreat at PoHo attended by 30 meeting members; also the work of several key committees and the thoughtful, thorough guidance of Judy Fetterley, clerk of the QQ Planning Committee and Barbara Spring. “Most importantly,” says Betsy, “it has strengthened our community.”

The NYYM Black Concerns Committee draws our attention to events in 2012 marking the 100th anniversary year of the birth of Bayard Rustin, a former member of 15th Street Meeting, who is acknowledged as the primary influence behind Martin Luther King’s adopting Gandhian nonviolent tactics. Resources are available at http://bit.ly/znWEw3. Of special note is the release in March 2012 of a new book by Michael Long, I Must Resist: Bayard Rustin’s Life in Letters. Book signings are scheduled for March 15, 7 pm, at 15th Street Meeting and March 21, 7 pm, at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. For further information contact Helen Garay Toppins, office [at] nyym.org.

Great news! Following a long weekend of intensive training in Alternatives to Violence Project (AVP) conflict-transformation skills at Chatham-Summit Meeting, January 27-–29, there are now 18 more potential AVP facilitators in New Jersey. According to Jill Nanfeldt of Chatham-Summit, “virtually all participants thought that it was so successful, they want to take the Advanced workshop,” which Jill hopes to schedule at CSMM by this summer. For more information about AVP in northern New Jersey, contact Jill at jillnanfeldt [at] mac.com.

“Friends on Fire” is the theme of Farmington-Scipio Regional Meeting’s (FSRM) Spring Gathering the weekend of April 20–22 at Long Point Camp in Penn Yan, NY. The gathering’s focus is intent on advancing a growing awareness within the Yearly Meeting of Friends who possess the gift of ministry, and the need to have these Friends and their gifts lifted up. FSRM welcomes Friends from outside the region and suggests registering well ahead of time. Contact Greta Mickey for the registration form, greta.mickey [at] gmail.com or 607-243-5668.

On Saturday, Feb. 11, Perry City Friends and families kicked up their heels, having fun and raising funds for their meeting all at the same time. Festivities began at 6:30 p.m. with family games and dances followed by contra dancing to American/bluegrass music from Miller’s Wheel Band.

Poughkeepsie Friend Fred Doneit calls our attention to a powerful weekend at Powell House March 30–April 1, an expanded version of the Awakening the Dreamer Symposium. The weekend provides a unique opportunity for Friends to explore a bold vision for bringing forth “an environmentally sustainable, socially just, and spiritually fulfilling human presence on planet Earth.” Says Fred, who is a trained Symposium facilitator, “My personal attraction to the symposium was its clear message, its recognition of the social- and economic-justice issues that environmental sustainability is dependent on, and its optimistic view of the possibilities that could be realized by ordinary citizens.” To register contact PoHo at 518-794-8811, www.powellhouse.org or info [at] powellhouse.org.

Focusing on strengthening regional and intergenerational relationships, All Friends Regional Meeting (AFRM) has organized an Arts Day for Saturday, March 24, from 3 to 7 p.m. at the Chatham-Summit meetinghouse. Working side by side, adults and children will be experimenting with clay, fabric, and paper and experiencing the joy of creativity and downtime together. AFRM Friends are encouraged to RSVP by March 14 to give time for planning food and art materials. Contact Nathalie Bailey at nbailey555 [at] verizon.net.